Water is one of the Earth’s most valuable resources. Some of us take drinking water for granted, while millions of people across the globe can’t even imagine having everyday access to clean water. This is a success story about a project in Liberia that began in 2015, where nonprofits joined forces to map the entire country and reach a common goal: bring clean drinking water to every Liberian household by December of 2020.

The results so far are amazing, to say the least, a 95% reduction in symptoms for water-related illness.

Learn about methods used to achieve project goals and amazing results that drastically changed people’s lives in Liberia.

Case Study Outline:

- The Origins of The Project

- Water Pollution and Socio-Economic Situation in Liberia

- A Plan to Bring Clean Drinking Water to Every Liberian Household

- Getting the NGOs Together and Overcoming Challenges

- Field Data Collection – Multiple surveys analyzed in a single map & data workspace

- The Results: Significant Health Improvements and Ensured Further Funding

The Origins of the Project

It all started with Darrel Larson, International Director of Sawyer Products and the founder of Give Clean Water nonprofit initiative, and his mission to bring clean water to remote parts of the world.

In 2008, Darrel wanted to make a difference in the world and help those in need, and as he was aware that contaminated water consumption was one of the biggest problems in the world, he decided to try bringing clean drinking water to people living in remote areas and struggling with illness. He chose Fiji because he had great relationships and a network of people there. The goal was to bring clean drinking water to everyone by installing water filtration systems.

Water pollution is the number one cause of water shortage and one of the biggest problems of the modern world. Almost 50% of the Fijian population didn’t have access to clean water before this initiative many years ago. The success of the project in Fiji acted as a proof of concept which Darrel could expand to other countries like Liberia, a country with almost no access to clean drinking water.

Darrel teamed up with The Last Well, an NGO that had experience in clean water projects. The idea was to bring a water filtration system to every family in Liberia, as the polluted drinking water was making people ill, with symptoms like diarrhea, headache, and cough.

With a GIS solution in the cloud, mapping households and available water sources, managing the delivery of water filters, and using collected data to eradicate water-borne sickness and diminish death rates, was no longer an impossible effort. GIS helped to create a sustainable solution that brings clean drinking water to people in remote areas.

What made it all possible was the GIS Cloud Mobile Data Collection app. It enabled the NGOs to conduct multiple surveys, manage people in the field as well as to track the process, and make decisions during the project. Keep on reading and learn how a few NGOs managed to make such a massive impact.

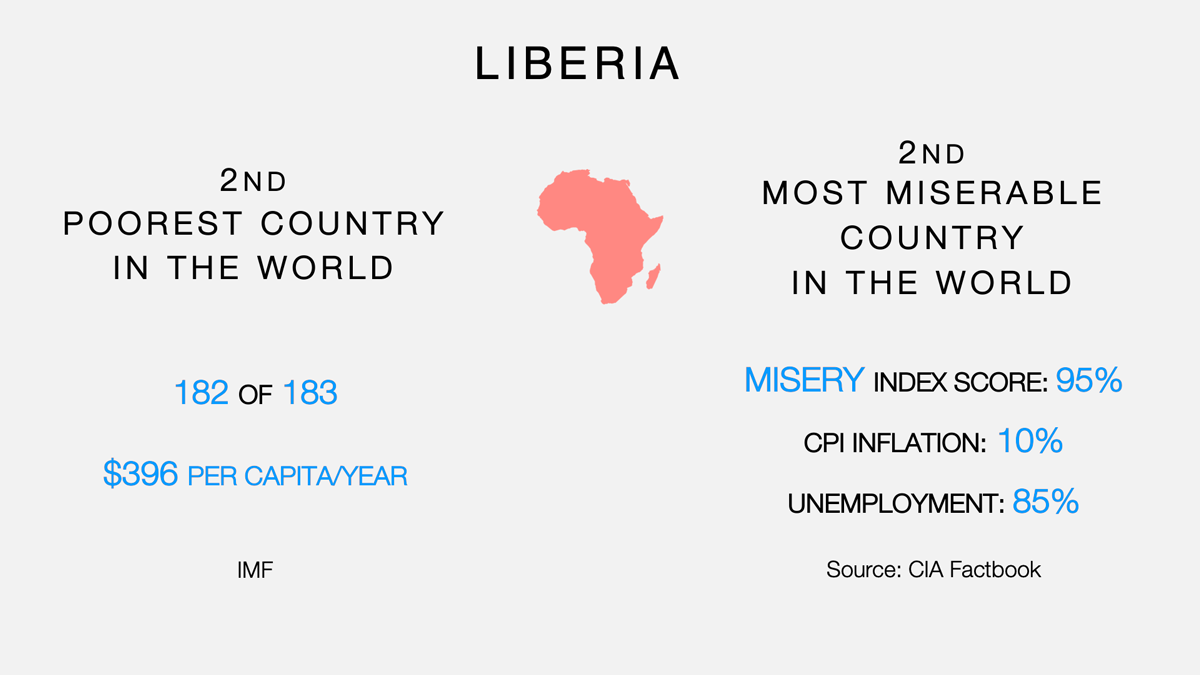

Water Pollution and Socio-Economic Situation in Liberia

The facts about Liberia are grim, to say the least. It is rated the second poorest and second most miserable country in the world. Take a look at the stats provided by the IMF and CIA Factbook.

In the last three decades, two civil wars that lasted for almost twelve years decimated Liberia. Peace was reestablished in 2003, marking the political end of the conflict and the beginning of the country’s transition to democracy. The number of casualties ranges from 150 000 to 300 000. Several years ago an Ebola outbreak took 10 216 lives in Liberia and neighboring countries in just twelve months.

What’s unbelievable is that the water-borne illness in Liberia tops the civil war as well as the Ebola outbreak. There were 300 000 deaths to water-related diseases since the end of the civil war. That’s up to 100 deaths per day in Liberia alone. The water in Liberia was contaminated across the country, and the people would drink water from bacteria-infested rivers and lakes.

Clean water still is the greatest physical need in Liberia. That’s why this project has such a drastic impact on the local communities.

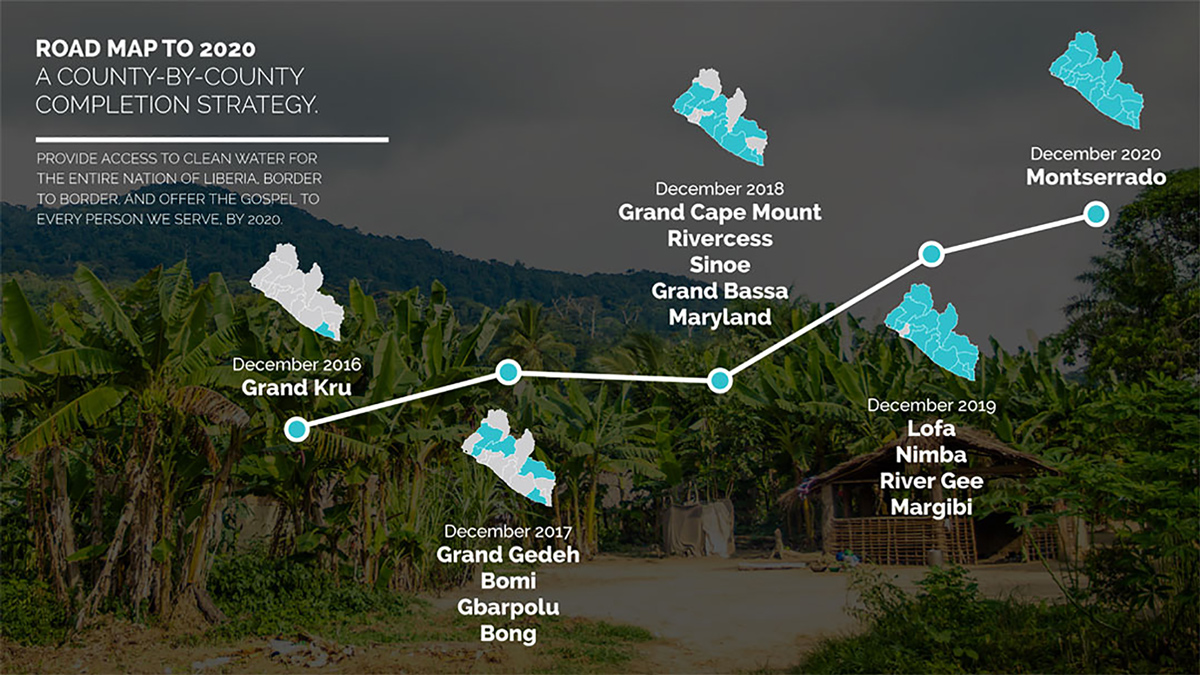

A Plan to Bring Clean Drinking Water to Every Liberian Household

After a successful project in Fiji, Darrel wanted to go to the most challenging place to make the most impact, so he joined The Last Well, who at that time already worked on bringing clean drinking water to the whole country of Liberia and was installing wells across the country.

As wells installation wasn’t always possible, or those wells weren’t accessible to all residents, Darrel brought the Sawyer water filters into the picture in 2015. Liberia was in dire need of clean drinking water, both wells and water filters were necessary to improve the health of the citizens.

The water filters were a donation from a US company called Sawyer Products that in 2015 provided 100 000 units with the help of an anonymous donor, and Darrel became an International Director of Sawyer Products, making all this possible.

The water filters clean 99.9999% percent of bacteria from contaminated river water,

can filter about 1 liter of water per minute, and last for 10 years.

This means that people living in remote parts of Liberia can produce clean drinking water from local water sources by themselves.

Bringing thousands of filters to remote villages located in a jungle and assessing their impact is as difficult as it sounds. To make things happen, they needed dozens of volunteers to install the filters and collect data. Darrel organized and led the GIS data collection with a mobile app that involves country-wide county and household surveys, tracking thousands of drilled wells, and most importantly tracking the distribution of clean drinking filter systems. Conducting surveys was essential after the filters were in place to see if there were any improvements in the health of the locals. They would perform follow-up surveys 2 weeks after the installation as well as 8 weeks after.

As this was a comprehensive project including entire Liberia, the team from The Last Well had to organize a large number of volunteers across the country and round up other NGOs working on water projects.

Getting the NGOs Together and Training Fieldworkers With No GIS Experience

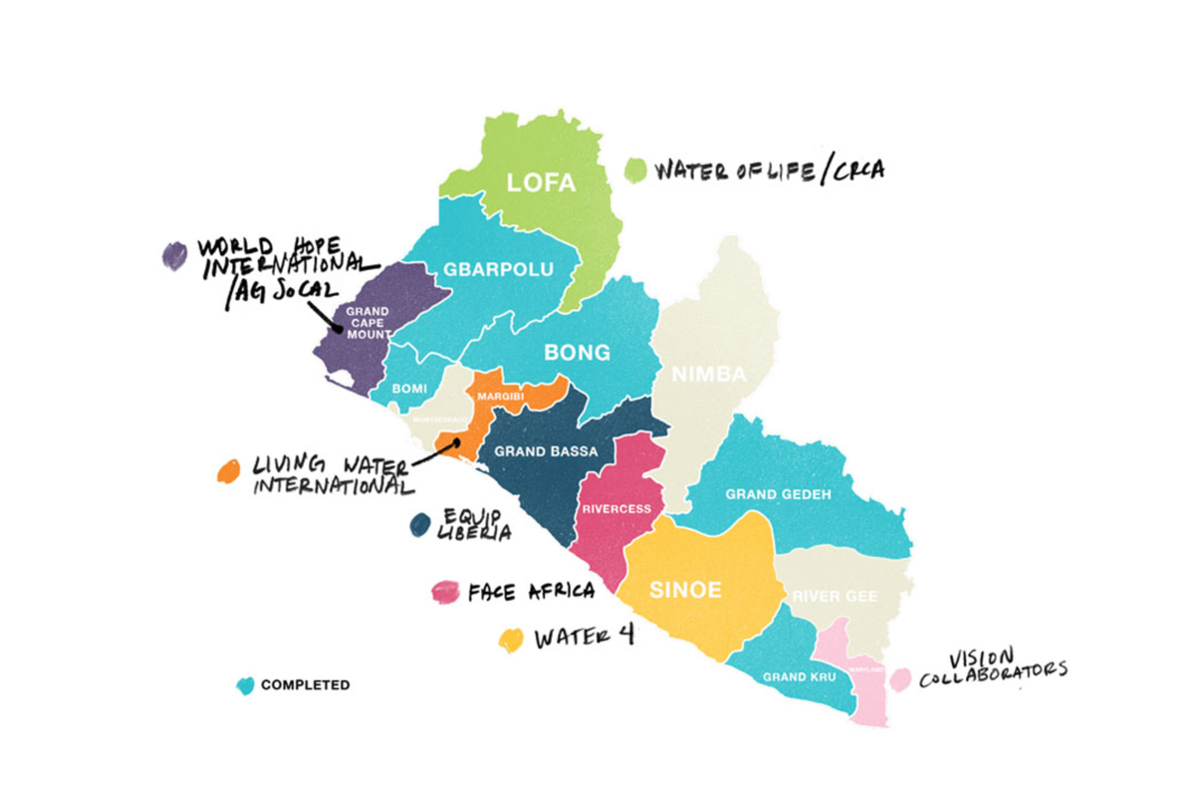

When The Last Well came to Liberia, they found out that many people and organizations were already working on clean water projects. The problem was that their efforts were scattered across Liberia and they didn’t define a unique goal. Eventually, they managed to round up all of the NGOs together as partners. They divided the country into 15 counties and assigned the exact locations each organization would focus on.

It was essential to collect quality data about the locations of households and settlements, information on people’s health and illness symptoms, data about water access, and water quality. Unfortunately, the census data they got from the government wasn’t accurate. So, it was necessary to map the villages and have a data collection process in place.

Training the volunteers and local people to use a digital mapping solution could have been another challenge, but it proved to be fast and effortless. They needed to train lay people, some using tablets for the first time, to install water filters and collect field data. The good thing was that the GIS Cloud Mobile Data Collection app was very user-friendly, in Darrel Larson words:

The app was so user-friendly that we didn’t have to hire an engineer. My challenge was, how can I harness the power of this technology without being an engineer. Then I found GIS Cloud.

Mobile Data Collection has changed my entire work process. What I love is the simple user interface. GIS Cloud has done all the heavy lifting of coding and made a very user-friendly solution for me.

Not only did the team from the Last Well and Darrel train 150 Liberians with no previous GIS experience in just a few months on how to use the app, and 30 of them on the very first day, but they also equipped around 20 Liberians with the knowledge to teach others. That way, Liberians are the ones running the project and can continue the good work when the NGOs pull out.

All in all, around 150 volunteers did a massive amount of fieldwork even in remote areas. Using canoes and ferry to cross rivers, hike as far as they can into the bushes, venture for 4 to 6 hours in the middle of the jungle to bring drinking water to small remote villages that nobody would pay attention to.

Field Data Collection – Multiple surveys analyzed in a single map and data workspace

To distribute 100 000 water filters and track their impact, they needed a sound field workflow. The team from The Last Well wanted to map the villages and water filter locations, track surveys, and get insight from the data.

Back in Fiji, Give Clean Water was using paper forms and GPS units for data collection and started looking for a more streamlined solution. Bringing paper forms back to the office, entering data into an excel spreadsheet with a lot of overlapping was time-consuming. The paper workflow takes a long time, and the field teams are holding onto paper and notebooks. Imagine 100 000 sheets of paper. They found the GIS Cloud software in 2012 when working in Fiji, which enabled them to digitize their workflow and reduce the paper workload.

The apps saved us a lot of paperwork and time. The power of this technology is radically transforming the efficiency by which nonprofits can deliver life-changing interventions around the world.

Darrel Larson, Give Clean Water

They were aware of some solutions, but they found GIS Cloud as the most convenient as it was so user-friendly. It allowed them to collect data on existing water resources and people’s health conditions to assess where to install the filters.

Volunteers go out equipped with tablets or smartphones, to areas with no internet connection, and collect data with the Mobile Data Collection app. Then the teams come back to a wifi area, hit a button on their tablets, and all of the data uploads to a server. The collected data can be shared and instantly accessed across different kinds of devices, web and mobile, so people in Liberia, staff in the US, anyone helping to run the project can immediately see collected data on a map and project status.

If we didn’t have a tool like this – I don’t think we could have done it. Technology is rapidly impacting the nonprofit world in great ways. What used to take hours, days, weeks, or months, to share data through handwritten forms, then transferring them to Excel worksheets, now can all be shared in real time using GIS technology.

Darrel Larson

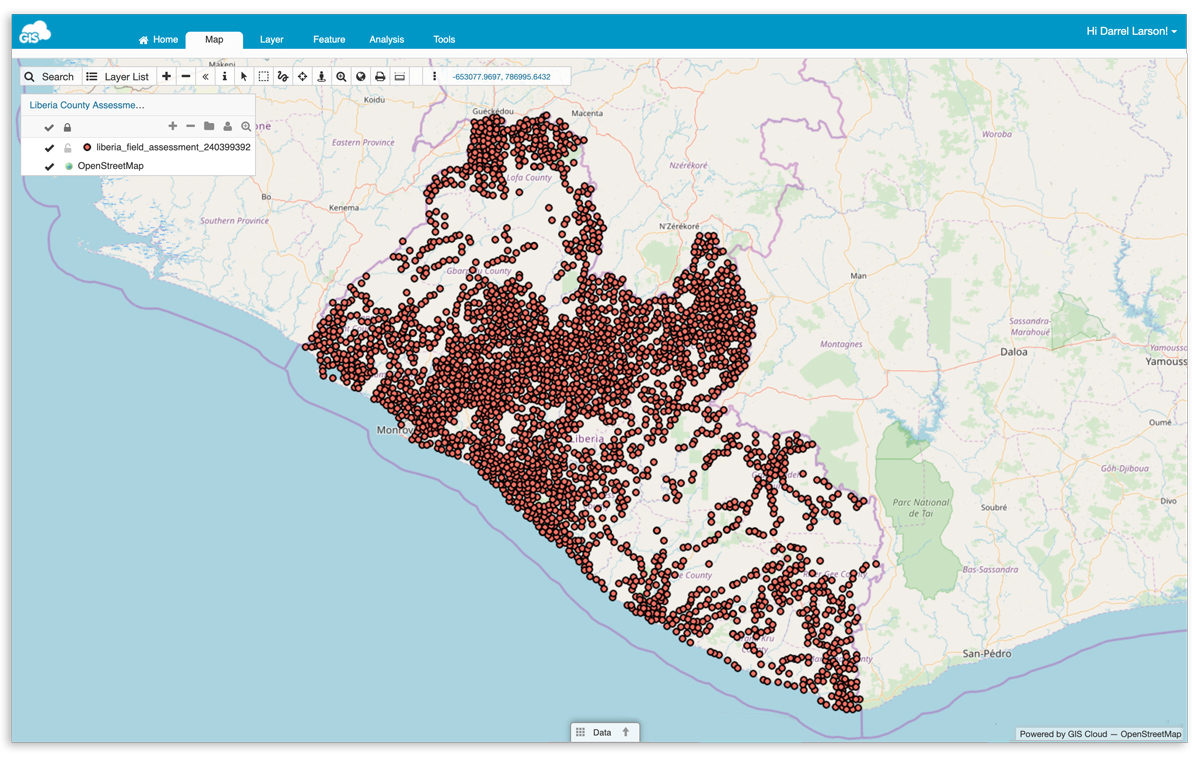

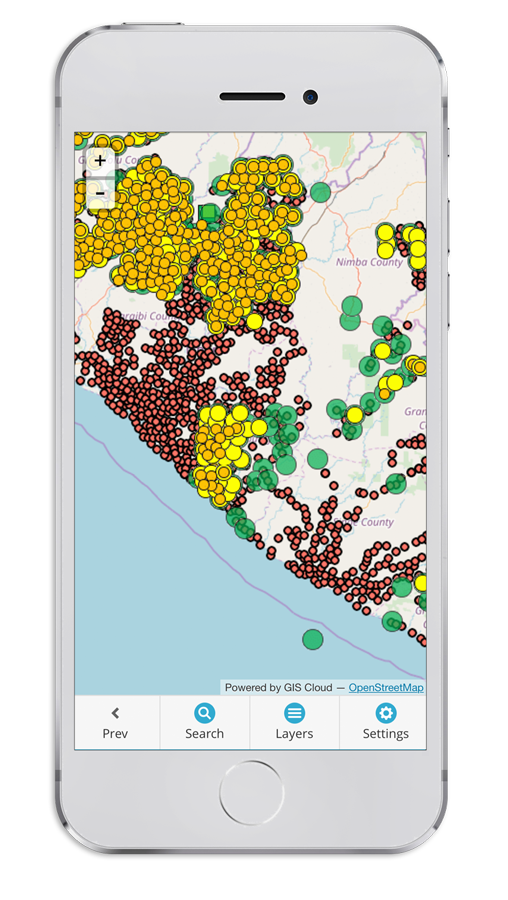

1. Village Assessment (census) and water resources mapping

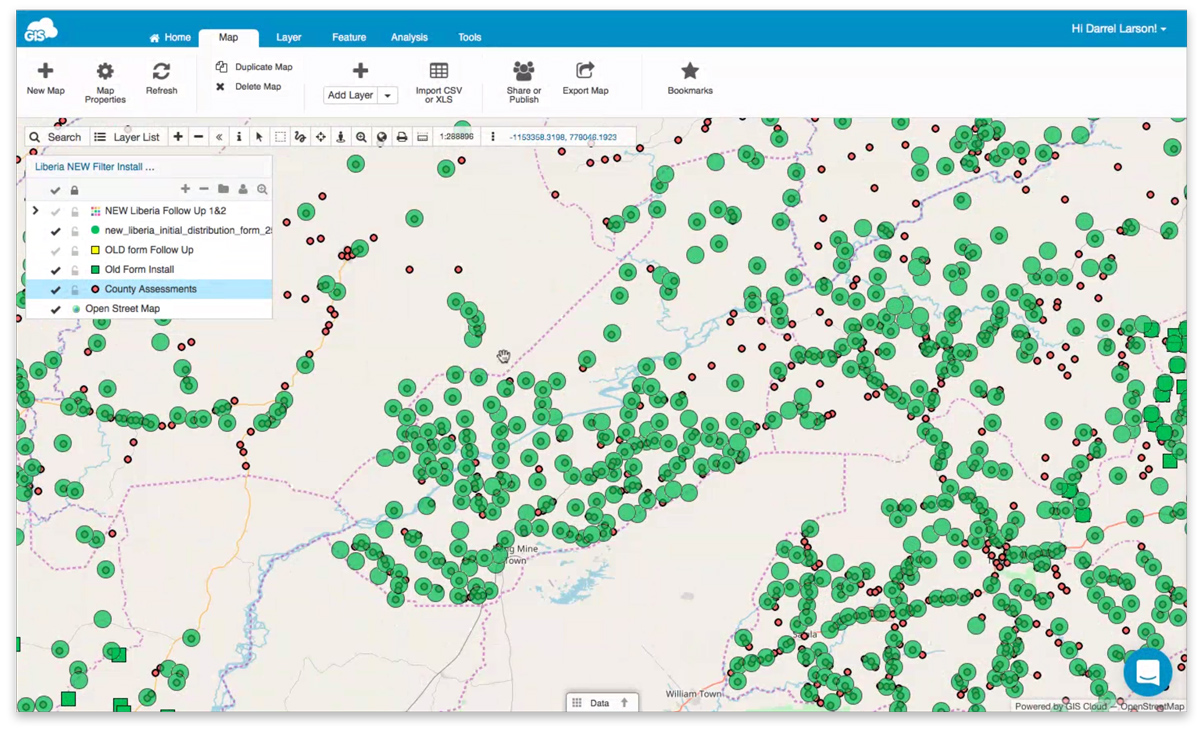

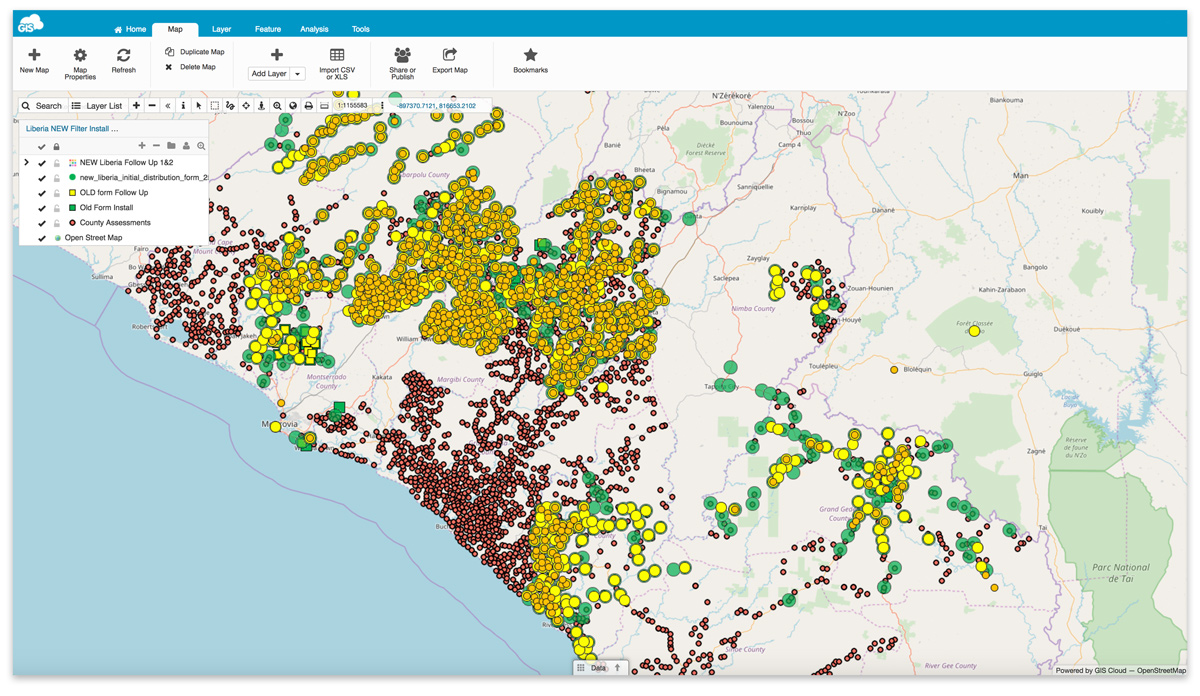

First, NGOs needed to map the villages and get a rough assessment of their water resources status (red dots on the map below). They mapped the locations of villages, their size, number of households, well presence and similar data.

2. Filter Installation and Initial Survey

The next step was to install the water filters and take the first survey on the people’s health (marked with green dots). When a team goes into the field, they install a water filter with a unique barcode and record the data about the installation by filling in one of the mobile forms. This way they can know exactly when, where and which filter was installed.

That’s where they get the baseline data like:

- household location,

- how many people live in the family,

- how many adults,

- how many children,

- how many cases of diarrhea,

- spend on purchased water,

- the medical cost to water-borne illness,

- school and workdays missed, etc.

3. Follow Up Surveys on People’s Health

The teams did a follow-up survey 2 weeks after the filters have been installed, to track if there’s any impact from the water filter installation (yellow dots). They collected the same data as the first time to get the before and after picture, to see if there are any improvements in people’s health. They also conduct the same survey 8 weeks after the filter installation to see the long term benefits (orange dots). This data is the foundation for further analysis of how water filters impact Liberian communities.

Overview of the field data in Map Editor.

The Results: Significant Health Improvements and Funding

The Last Well said that the collected data was the game-changer. The ability to collect data, quantify the actual results, and analyze the data with the help of scientists from Calvin College made all the difference. Not only did GIS technology allow the tracking of the filter installations and follow-up surveys, but robust health and socio-economic data was also collected. The data shows life-changing benefits of installing water filters, like diarrhea reduction, medical savings, water savings, missed school and work days reduction, after the water filter installation.

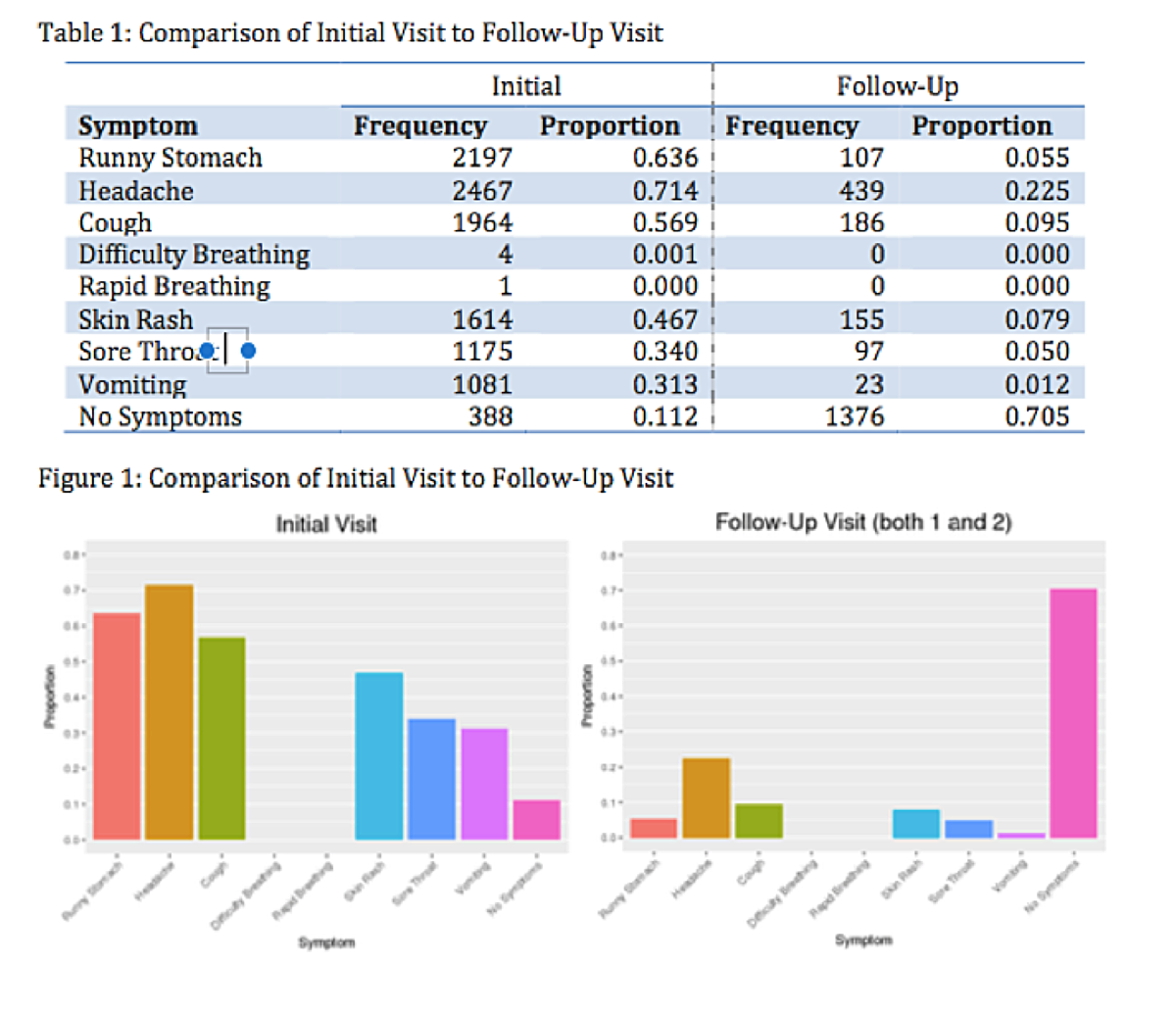

The results are no less than amazing. In the first 25,000 households analyzed, 2,197 had reported cases of diarrhea. After a two-week follow-up, that number was down to 107. A second follow up after eight weeks reported another slight decrease in diarrhea reduction. Here’s a comparison of the initial visit and the follow-up.

Not long after the first results came in, the Grand Kro county got border-to-border clean water and received a certified completion letter. That never happened before, so the government went in and checked the collected data to verify it, and they certified the letter. It was a game-changer for the country.

If we can finish a county, we can finish the entire country.

Todd Phillips, Founder of Last Well

These results are a product of drilling wells across the country and installing 40 000 filters up until 2018, ending that year with 75 000 families equipped with water filters. With plans to cover the last 20% of Liberia by 2021. To learn first hand about this project from Darrel, watch this extensive webinar where Darrel was our guest

.

The NGOs continue to methodically make accessible clean water in Liberia with the help of about 100 volunteers. The volunteers are Liberians and are capable of sustaining the project by themselves, even when the NGOs pull out.

Not only that clean drinking water was made available to residents across the country, even in some small villages that were discovered during the mapping process, but the health of the people improved drastically over a small time period.

Mapping of households and people’s condition, in the end, resulted in a country-wide census, accepted as official data by the government. This also ensured further funding of the project as data was presented clearly, with spatial information and photos as proof.

Interested in the GIS Cloud solution for NGOs and Nonprofits? Contact us, we’ll be more than happy to give you a live demo.